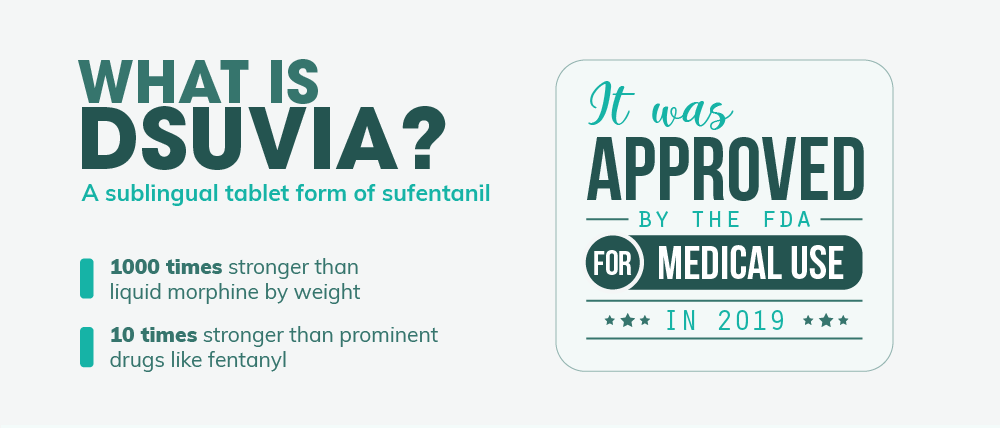

In a move that has medical watchdogs, media outlets, and the public at large in a bit of an uproar, the Food and Drug Administration recently approved a powerful new opioid for medical use in early 2019. Dsuvia, a tablet form of sufentanil developed by AcelRX, is many times stronger than liquid morphine and 10 times stronger than the notorious fentanyl – a compound that’s largely been to blame for a recent surge in deadly opioid overdoses. And as the death toll from opioids like fentanyl continues to rise (it nearly crested 30 thousand in 2017 alone), many critics of the approval are left wondering, is greenlighting another over-powered opioid really what we need right now?  Combined with concern over a questionable (and some might even say suspicious) approval process, Dsuvia’s release could be the first step in a drug crisis that’s bound to get a whole lot worse.

Combined with concern over a questionable (and some might even say suspicious) approval process, Dsuvia’s release could be the first step in a drug crisis that’s bound to get a whole lot worse.

“Get the help you need today. We offer outpatient assistance, so you can maintain your work, family, and life commitments while getting the help you deserve!”

Dsuvia: Easier Access to a Staggeringly Potent Opioid

So, what is Dsuvia and what makes it so different than what’s on the market today? Well, Dsuvia is a narcotic analgesic – basically an opioid drug that’s used to reduce moderate to severe pain in patients. Other narcotic analgesics you’ve likely heard of include Vicodin, OxyContin, Dilaudid, Demerol, and Lorcet. Dsuvia’s active ingredient is sufentanil which is chemically similar to and stronger than fentanyl, another powerful opioid pain reliever. Sufentanil has been used in the medical community for quite some time. It was first synthesized by Belgium’s Janssen Pharmaceutica in 1974 and approved for use in 1984. And among opioids meant for use in humans, it is the strongest pain-relieving compound by weight. Its potency makes it ideal for surgical use and in post-surgery care. Added to that, it has the highest affinity for opioid cell receptors, making it an effective pain reliever for opioid-dependent patients taking drugs like buprenorphine. However, until recently, sufentanil has only been administered intravenously. Dsuvia, on the other hand, is a sublingual tablet – a pill placed under the tongue that then dissolves within just a few minutes. This method of administration bypasses a number of difficulties associated with IV use, such as:

- Inability to find a vein (especially in elderly or obese patients)

- Discomfort of patients

- Improper dosing

- Possible complications and infections of the skin

On top of that, IV sufentanil was only used under the care of a licensed and certified anesthesiologist or anesthesia care provider. With Dsuvia, on the other hand, the administration is far easier to perform and may open the door to use among general practitioners and nurses. The small, plastic dispenser simply needs to be placed inside the mouth, aimed under the tongue, and the plunger depressed to release the single dose pill. After that, the dispenser is thrown away – easy as that.

How Powerful Is Sufentanil?

One of the biggest concerns among critics of Dsuvia is the fact that its main ingredient, sufentanil, isn’t your everyday narcotic painkiller. In fact, it’s actually one of the strongest analgesics on the market today. Sufentanil is so potent that it’s actually 1000 times stronger than morphine by weight. To give you a better idea of how other opioids stack up, below is an opioid equivalency chart comparing the potency of certain drugs to morphine (by weight).

- Codeine: 1/3 as strong as morphine

- Hydrocodone: Equivalent to morphine

- Oxycodone: 50% stronger than morphine

- Methadone: 3 times stronger than morphine

- Heroin: 2 to 5 times stronger than morphine

- Buprenorphine: 40 times stronger than morphine

- Fentanyl: 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine

- Sufentanil: About 1000 times stronger than morphine

- Carfentanil: Up to 10,000 times stronger than morphine

Why Was Dsuvia Developed?

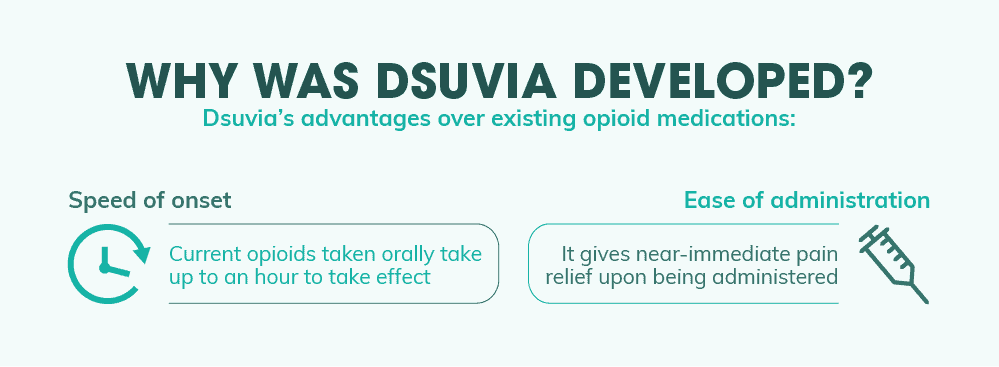

With all the various opioid pain reliever drugs on the market today, what makes Dsuvia different? Why can’t patients just use one of the literally hundreds of other opioids already available? This is one of the main questions opponents of the new drug have been asking the FDA and the drug’s manufacturer. And according to them, Dsuvia fills a specific need that other opioid formulations just can’t meet. The first is the speed of onset. Many other opioid drugs on the market today are quite effective at reducing pain. But the vast majority of them are in the form of orally administered pills. This means that they often take anywhere from a half of an hour to an hour to start taking effect. And for some, this wait time is far too long to meet the needs of the patient or the physician. That brings us to the second reason Dsuvia manufacturers developed the drug – ease of administration. For near-immediate pain relief, many doctors employ opioids intravenously. This allows the drug to reach full effect within seconds without its effectiveness being stymied by the body’s natural filtration organs (liver, kidneys, etc.). However, IV medication use has a number of drawbacks that make it less than ideal for certain kinds of patients as well as certain kinds of situations. And one situation in particular – that of an active battlefield – makes IV administration especially difficult. Dsuvia’s ability to simply dissolve under the patient’s tongue, then, makes administering the drug far easier than intravenous treatment without sacrificing the onset speed of its pain-relieving properties.

Dsuvia’s Place on the Battlefield

Were it not for the Department of Defense, Dsuvia may have never been developed in the first place. Originally, AcelRx’s flagship project was the development of Zalviso – a self-administered pain relief system for use in post-surgery care. Similar to IV morphine systems controlled by patients, Zalviso administers a single sublingual sufentanil tablet (at half the dosage of Dsuvia) to help manage pain symptoms. Patients are free to re-administer again according to a specific time period if symptoms persist, but the device also prevents overuse as well. The system is currently legal in Europe and is still undergoing clinical trials for approval through the FDA. However, during Zalviso’s development, AcelRx was approached by the U.S. Department of Defense to create a new product for acute pain management – one that was twice as strong as Zalviso’s sufentanil dosage, but that also featured a simpler method of administration. And to make the decision even easier, the DoD offered a hefty funding package of up to $20 million to develop the product. According to AcelRx co-founder Dr. Pamela Palmer, the Army’s contract “will actually allow sublingual sufentanil to be used by more patients in more settings.” And while a wider availability might make it easier for physicians to treat certain conditions, it can also end up opening a Pandora’s Box for a population that’s already dangerously addicted to prescription opioids.

An Unusual Approval Process…

Approving the use of an opioid medication in the midst of a drug crisis is unusual on its own. And many common-sense advocates are calling for reconsideration of Dsuvia’s approval on this basis alone. But the controversy surrounding the drug’s release also stems back to the method in which Dsuvia was approved. To explain, when the FDA approves a drug for public use, the decision is made by a number of members from various backgrounds. And since not every voting member is a specialist in the field to which a drug’s use will apply, the group is usually informed about the implications of a decision by an outside expert counsel. Since 2002, the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee (DSRMAC) has helped inform the FDA on the safety implications of various drugs. Their expertise in drug safety, pharmacoepidemiology, risk management, and other areas helped provide a broader scope of consideration that voting members may not have had the specialization to truly understand. And in the face of the growing opioid epidemic, this committee, in particular, was designed to help the FDA keep the potential for abuse in mind. However, the full DSRMAC committee was not invited to the meeting. According to the Silicon Valley Business Journal, the full DSRMAC was included in all 12 of the approval meetings involving opioids from 2016 to 2017. But this year, only 3 out of the 7 meetings will include the complete DSRMAC. This is notable for two reasons. First, a more vocal consideration of the health implications of Dsuvia during the meeting may have swayed certain voters to deny the drug’s approval. And second, the DSRMAC members are often invited as temporary voters in the advisory committee. Had the entire DSRMAC committee attended, it may have resulted in a different outcome than the 10 to 3 passing vote that helped secure Dsuvia’s place on the medical market. In a letter penned by medical consumer rights advocacy group Public Citizen, the authors stated that “The FDA appears to have made a deliberate decision to avoid including the full DSRMAC in the review of sublingual sufentanil tablets in order to tilt [the] outcome of the AADPAC in favor of approval.”

Even Disapproval from the Committee Head

In addition to the unusual choice of the FDA to not include the full drug safety committee (which went against years of protocol), the committee head himself, Dr. Raeford Brown, has publicly spoken out against the approval of the drug. Voicing his opinion within the Public Citizen letter to the FDA, Dr. Brown wrote: Lack of historical ability of the FDA to enforce controls, the pharmacologic potency of the drug, and the ease with which this drug will be diverted are some of the reasons that I would never consider this product for marketing in the U.S. Sublingual sufentanil represents a danger to the general public health and will make our job of protecting Americans more difficult. Dr. Brown points to the failure of numerous safeguards that have been erected to prevent misuse of other opioid pain relievers as an indication of sufentanil’s risk of abuse. And despite the variety of controls that the FDA referred to in their decision, Brown believes that these measures won’t be enough to stop the eventual abuse of Dsuvia. “I predict that we will encounter diversion, abuse, and death within the early months of its availability on the market,” he writes. And if things go the way Dr. Brown expects, the opioid epidemic will become even worse than it is today.

“We treat both addiction and co-occurring disorders and accept many health insurance plans. Take a look at our outpatient program today!”

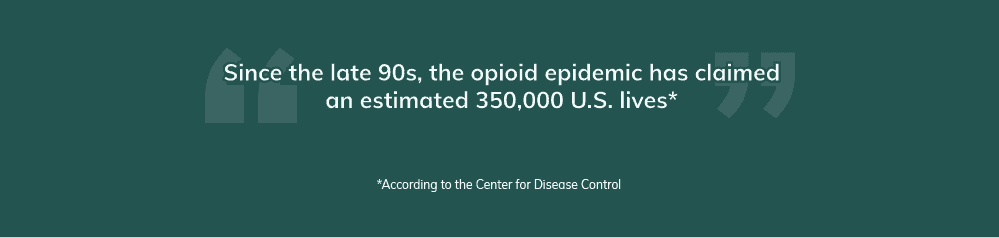

How Bad Has the Opioid Epidemic Gotten?

To put it lightly, it’s bad. Since it began in the late 90s, the opioid epidemic has claimed the lives of an estimated 350 thousand Americans. And every single day, more than 115 people die from a fatal opioid overdose according to the CDC.  Drug overdoses as a whole (largely fueled by opioid addiction) regularly kills more people than guns, car accidents, accidental injury, and even certain kinds of cancer. And since 1999, an estimated 630 thousand people have died of a drug overdose. In one year, the casualties from overdoses outnumbered the total U.S. military deaths from all of the Vietnam war, the Iraq War, and the War in Afghanistan combined – in a single year! And to make matters even worse, legislation for empowering states to fight back against the rising death toll is coming in a decade too late. It isn’t any surprise, then, that experts have called this the worst health crisis our country has ever seen.

Drug overdoses as a whole (largely fueled by opioid addiction) regularly kills more people than guns, car accidents, accidental injury, and even certain kinds of cancer. And since 1999, an estimated 630 thousand people have died of a drug overdose. In one year, the casualties from overdoses outnumbered the total U.S. military deaths from all of the Vietnam war, the Iraq War, and the War in Afghanistan combined – in a single year! And to make matters even worse, legislation for empowering states to fight back against the rising death toll is coming in a decade too late. It isn’t any surprise, then, that experts have called this the worst health crisis our country has ever seen.

A Comparative History of U.S. War Deaths

Sometimes the sheer scope of destruction can be hard to truly grasp. And given the hundreds of thousands of deaths the current drug epidemic has caused, it can be easy to disregard just how devastating the damage really is. Below are a few official U.S. death tolls from several major wars to compare to the total death toll from the drug epidemic beginning in 1999.

Drug Overdose Deaths since 1999: 630,000

Civil War Deaths: 655,000 Revolutionary War Deaths: 25,000 WW1 Deaths: 116,516 WW2 Deaths: 405,399 Korean War Deaths: 36,516 Vietnam War Deaths: 58,209 War in Afghanistan Deaths: 2,216 Iraq War Deaths: 4,497

Other Fast Stats on the Opioid Epidemic

Here are a few quick statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) to help put the breadth of the raging opioid epidemic into perspective.

- Around 46 people die from prescription opioids every single day in the United States according to historical data.

- Newer figures for 2016 estimate that as many as 89 people died from prescription opioids each day. This figure includes natural, synthetic, and semi-synthetic opioids.

- Synthetic opioids like fentanyl specifically are causing a rapid increase in overdose deaths. Death counts involving this drug (usually illicitly manufactured) spiked by 540% from 2013 to 2016.

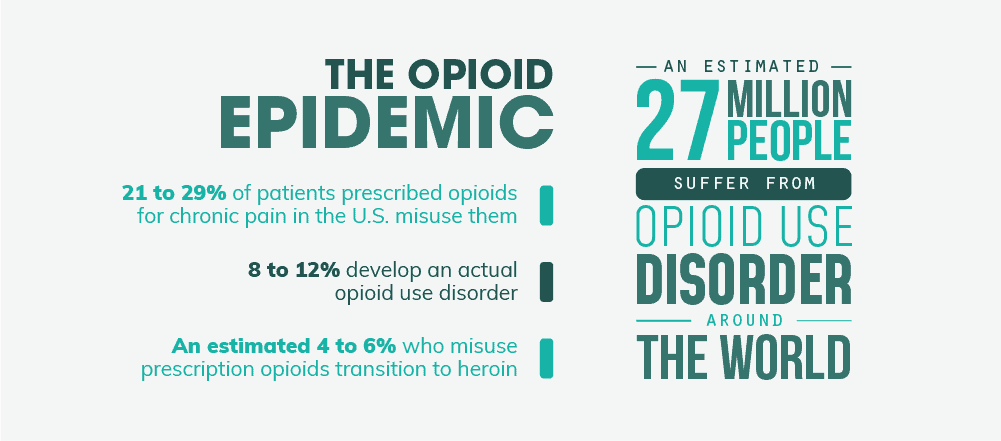

- Roughly 21 to 29% of patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain misuse them while 8 to 12% develop an actual opioid use disorder.

- An estimated 4 to 6% who misuse prescription opioids transition to heroin.

- In 2017, nearly 16 thousand people died from a heroin overdose. Almost 30 thousand died from illicit opioids like fentanyl.

- There were an estimated 27 million people who suffered from opioid use disorders in 2016 around the world.

- Driven largely by the worsening opioid epidemic, drug overdose is now the leading cause of death among Americans under 50 years old.

The 3-Stage Progression of the Epidemic

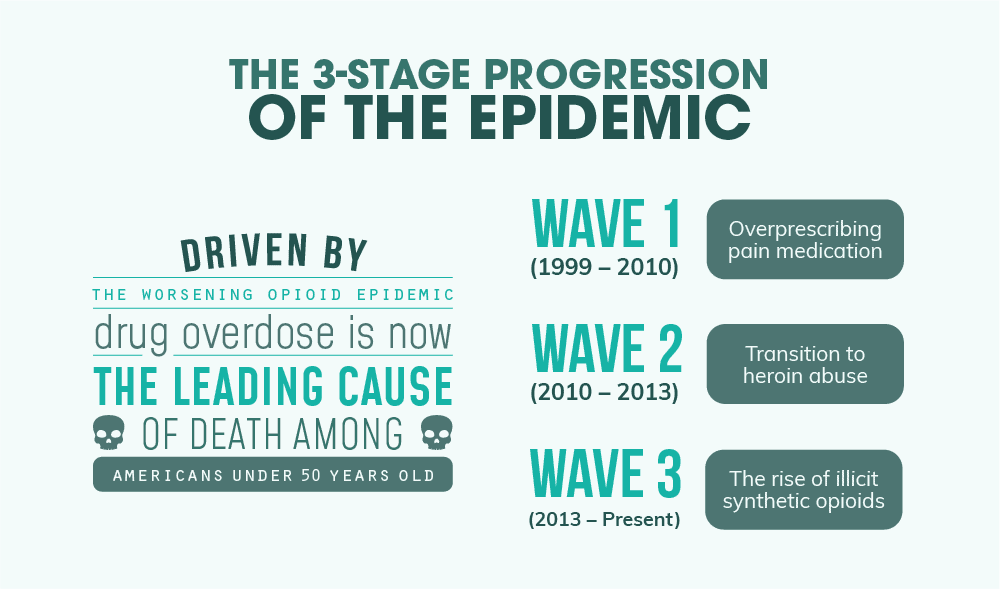

From its start in 1999, the opioid epidemic has morphed and evolved over time. And contrary to popular belief, not all opioid deaths are caused by a single drug like OxyContin. Instead, the epidemic at large has been characterized by organizations like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as having 3 distinct waves.

“We accept many health insurance plans. You can get your life back in order with our outpatient program today!”

Wave 1 (1999 – 2010) – Overprescribing Pain Meds

The very first wave of the opioid epidemic has to do entirely with the ineffectiveness of the pharmaceutical industry to 1.) recognize the true addictive potential of opioids or 2.) regulate overprescribing of habit-forming painkillers like oxycodone and hydrocodone. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), the origins of the crisis can be traced back to the interplay of four specific changes in the medical field:

- A regulatory, policy and practice focus on opioid medications as the primary treatment for all types of pain

- An unfounded concept that opioids prescribed for pain would not lead to addiction

- The release of guidelines from the American Pain Society in 1996 encouraging providers to assess pain as “the 5th vital sign” at each clinical encounter

- The initiation of aggressive marketing campaigns by pharmaceutical companies promoting the notion that opioids do not pose a significant risk for misuse or addiction and promoting their use as “first-line” treatments for chronic pain.

As a result of these four events, in particular, physicians began over-prescribing prescription painkillers like OxyContin without understanding the true addictive potential of the drugs. And that led to an increasingly opioid addicted population.

Wave 2 (2010 – 2013) – Transition to Heroin

As the number of opioid prescriptions began to drop as their addictive potential became known and restrictions tightened, more and more opioid-hooked users were left without easy access to a legally prescribed high. As a result, many resorted to stealing pills from others or illegally obtaining overlapping prescriptions via doctor shopping. However, many others turned their sights on a cheaper, more readily available drug being sold on the streets – heroin. A powerful opioid itself, heroin delivered a similar high without all the fuss of visiting a physician and lying to score another batch. The risk of transitioning to heroin from prescription pain relievers isn’t just conjecturing either. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), the incidence of heroin initiation was a whopping 19 times higher among prescription painkiller abusers compared to the normal population. And equally importantly, this trend of starting with prescription opioids and transitioning to heroin is a new development. More than 80% of people in treatment for opioid addiction in the 1960s started with heroin. By 2000, 75% of people receiving opioid addiction treatment began their drug abuse with a prescription painkiller. And according to some studies, as many as 80% of heroin users started their addictive habits with prescription opioids. Consequently, heroin overdose deaths went from around 2 to 3 thousand a year up until 2010 to over 10 thousand in 2014. As a result, the prescription opioid crisis also became a heroin crisis.

Wave 3 (2013 – Present) – The Rise of Illicit Synthetic Opioids

This phase of the opioid epidemic is where fentanyl comes onto the scene. 100 times more powerful than morphine and 50 times more potent than heroin, synthetic opioids like fentanyl were responsible for nearly 30 thousand deaths in 2017 alone. Given that it’s often mixed with other illicit drugs like heroin and cocaine to boost their potency, many substance abusers end up taking fentanyl-laced doses unknowingly. And that can often lead to far more overdose deaths as a result. While this drug has been used in the medical community for quite some time (mainly to provide powerful pain relief to cancer patients), it’s the illicitly produced version of this drug that often does the most harm. Also known as IMF, illicitly manufactured fentanyl comes primarily from China and Mexico. And while the number of fentanyl-related deaths has risen by as much as 540% in recent years, the CDC reports that prescribing rates for the drugs have remained quite steady during that time. The problem, then, appears to be synthetic opioids that have been illicitly manufactured, not an overabundance of these drugs that have been prescribed by a physician.

Recent Lives Lost to Opioids

The devastation that opioid addiction so often wreaks isn’t confined to urban streets or backcountry mobile homes – despite what most people think. In fact, the recent surge in substance abuse and addiction is actually disproportionately affecting younger, wealthier adults compared to the impoverished. Studies have even suggested that “by the age of 26, upper-middle-class young adults’ lifetime chances of being diagnosed with an addiction to drugs or alcohol were two to three times higher, on average, than the national rates for men and women of the same age.” It isn’t surprising, then, that the scourge of opioid addiction has seeped into the lavish lifestyles of the rich and famous too. Below are just some of the most notable celebrity deaths caused by opioid abuse and addiction.

- Heath Ledger

- River Phoenix

- Mac Miller

- Chris Farley

- Prince

- Phillip Seymour Hoffman

- Carrie Fisher

- Tom Petty

- Elvis

- Chris Penn

- Cory Monteith

- John Belushi

The Increasingly Infamous Synthetic Opioids

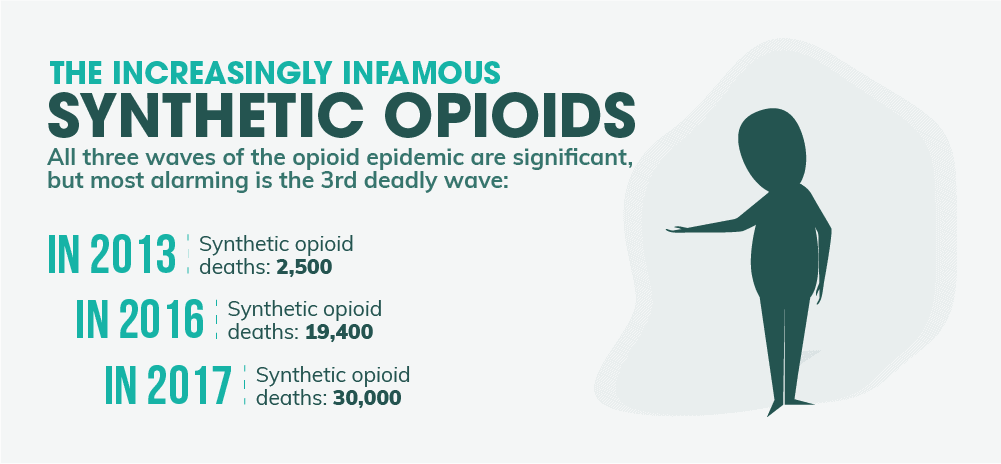

While all three waves of the opioid epidemic have played a significant role in the ever-rising death toll from drug overdoses, the third wave involving synthetic opioids is the most alarming. Not only is this wave exceedingly deadly, but it’s also spreading faster than many people might think. In 2012 and 2013, synthetic opioid deaths were at around 2,500 per year. In 2014, that number jumped to well over 5,000. And a year later, it nearly reached 10,000 deaths per year. From 2015 to 2016, the overdose deaths almost doubled again to 19,400. Almost 30,000 died in 2017. This is one of the sharpest death toll increases involving drugs the country has ever seen. And today, synthetic opioids like fentanyl almost kill more people per year than every other drug combined. What’s more, these drugs are actually so potent that even accidental inhalation or simply coming into contact with the skin can provide fatal results. This poses a unique threat to emergency medical personnel as well as law enforcement officers. And special training protocols have been created to help reduce this threat in particular.

What’s Driving the Surge of Synthetic Opioid Use?

One of the biggest factors in the ever-escalating synthetic opioid deaths is the fact that so many other substances of abuse are cut with or replaced entirely by these drugs. According to the DEA’s 2017 National Drug Threat Assessment, fentanyl is increasingly being mixed with low-grade heroin to boost its potency. Users then take the mixed product without knowing about the laced product which can more easily lead to a fatal overdose. On top of that, fentanyl is also being mixed with other drugs like cocaine, methamphetamine, or even counterfeit prescription pills for a more intense high. And again, street users rarely understand just how powerful these drug combinations really are. With the emergence of synthetic opioids on the drug scene, then, it isn’t just opioid overdoses that have risen exponentially – it’s most other drug deaths as well. Cocaine overdose deaths, for example, numbered only around 4,000 in 2010 with just 4% of these deaths involving synthetic opioids. But in 2016, more than 10,000 people died from a cocaine overdose – an increase of over 150% in six years. And even more, telling is that around 40% of those deaths involved synthetic opioids like fentanyl. Other drugs like benzodiazepines (anti-anxiety meds like Ativan and Xanax) are also being tainted more and more with synthetic opioids. Just 11% of benzo overdoses in 2010 involved synthetic opioids. By 2016, that proportion jumped to more than one-third. “People are assuming they’re getting their 10 milligrams of Percocet and they’re getting some amount of fentanyl or fentanyl analog that’s more potent,” said Christopher Jones, PharmD and program director at SAMHSA. It’s clear, then, that synthetic opioids aren’t just killing opioid users – they’re making nearly every class of drug significantly more dangerous too.

Types of Synthetic Opioids Being Abused

Today, there are over 1400 different fentanyl analogs and derivatives that have been described in medical literature or used illicitly on the streets. A recent move by the DEA has placed all fentanyl-related substances in the Schedule I class of illegal drugs as a response to the growing death toll. Below are just some of the most common synthetic opioids being used on the streets today, along with links to overdose reports concerning each drug in particular.

- Fentanyl – 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine.

- Carfentanil – 10 thousand times more potent than morphine. Typically used as a veterinary pain medication.

- Acetyl-fentanyl – 15 times more potent than morphine.

- Butyrfentanyl – 30 times more potent than morphine.

- U-47700 – 12 times more potent than morphine.

- MT-45 – Equivalent to morphine.

How Is (and Isn’t) Dsuvia Safeguarding Against Abuse?

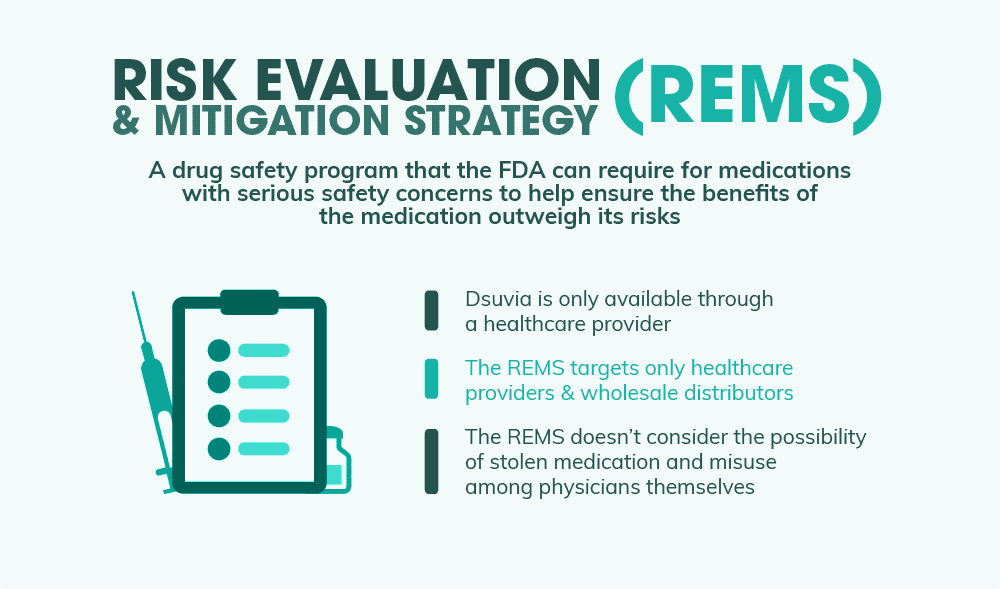

The opioid epidemic is without a doubt one of the deadliest health crises this country has ever seen. So the question is, how the heck does the FDA square the approval of Dsuvia, a new type of synthetic opioid, with the rising death toll linked with opioid abuse across the U.S.? One commonly-cited reason is that Dsuvia fills a unique need that isn’t being met by other medications available today. The easy-to-use delivery device makes it ideal for situations where IV administration is problematic, especially on the battlefield. Another reason that the FDA points to is that Dsuvia will have a comprehensive set of abuse prevention strategies as outlined by its Risk Evaluation & Mitigation Strategy, or REMS.

Risk Evaluation & Mitigation Strategy (REMS)

The Dsuvia REMS was created to ensure that the drug’s benefits outweigh its risks. As Dsuvia is only approved for use by an approved healthcare provider (and can’t be obtained by patients from a pharmacy), there are two types of targets for the REMS: healthcare providers and wholesale distributors. Each of these targets has their own requirements for being able to distribute or use Dsuvia. Healthcare providers, for example, have to be trained in the correct administration of the drug, as well as where it can legally be administered, among other things. Dispensers must only distribute the drug to licensed healthcare providers and must maintain and submit records of all Dsuvia shipments to AcelRx Pharmaceuticals. The FDA believes that this REMS will be enough to curb abuse of Dsuvia in the future and will outweigh and risks that the drug poses to the public.

Why Dsuvia’s Safeguards May Not Be Enough

As Dr. Brown points out in his article, Dsuvia’s risk mitigation strategies don’t necessarily ensure that these powerful pills won’t end up in the hands of abusers. And there are two weak points in particular that the FDA doesn’t seem to have considered: the possibility of stolen medication and misuse among physicians themselves.

- Stolen Medication – While Dsuvia can only be administered by a trained professional, it can still be stolen from hospitals and other healthcare providers.

According to SAMHSA, only about 0.7% of people who abused prescription opioids stole them from a healthcare provider. And while that doesn’t seem like much in the grand scheme of things, that translates to as much as 80 thousand people considering the 11.5 million people who abuse these drugs every year.

On top of that, 6% bought them from a drug dealer who may have gotten his supply from a batch stolen from a healthcare provider.

In the end, even if stolen medication isn’t the most common means of procuring prescription opioids, it still happens quite a lot more than most people think.

- Misuse Among Physicians – Administering physicians themselves may also end up being abusers of the drug. In Dr. Brown’s letter to the FDA, he notes numerous personal experiences where he has watched as trained professionals succumbed to the life-shattering effects of addiction. And to him, he doesn’t think Dsuvia will be any different.

And indeed, studies have shown that physicians are at a significantly higher risk of abusing opioids than the public in general. According to one study in the American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, the rate of opioid abuse among physicians is 5 times higher than other professions.

Barring general public access to the drug is one measure of prevention. But it doesn’t necessarily protect the doctors and nurses themselves from misusing or even selling Dsuvia to others.

A Shaky Decision & An Uncertain Future

With the FDA’s unconventional approval of Dsuvia, the powerful new opioid is set to hit hospitals in early 2019. And with its arrival on the medical scene, it may open up the door to a new wave of abuse, opioid addiction effects, and overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids. The decision of the Food and Drug Administration to greenlight Dsuvia calls into question whether or not the federal safety organizations designed to protect the public are really considering the full scope of the opioid epidemic, one of the worst health crises our country has ever seen. And if they are, how many more deaths will it take to set up more stringent approval guidelines for these powerful narcotics? Time will only tell if the safeguards surrounding Dsuvia are enough to prevent abuse. But one thing’s certain: despite the ever-raging drug epidemic, the number of powerful and potentially life-threatening opioids being used just got a little bigger.

What Did you Think About This Blog?

Give it a Rating!